AlphaGo-style Learning in Connect Four

Last year, for my group final project for Prof. Torralba’s “Advances in Computer Vision” class, we decided to try and see whether we could create a system to learn to play Connect-Four. Our project write-up is available here.

Put simply, our goal was to train an algorithm that would take in a synthetically-generated image of a Connect Four board and an identity (red or black), and output a “move” corresponding to the column in which to place the next token. The “quality” of such a gameplaying agent is relative: we consider algorithm A better than algorithm B if on average across several games, an agent playing algorithm A wins more times than an agent playing algorithm B.

The reason we picked Connect Four is that it’s a long-horizon game with fairly sparse rewards (just win/loss/tie upon game conclusion). That meant that it was particularly suited to model-based planning, and less susceptible to model-based RL approaches. In that sense, Connect Four is a much smaller, much simpler version of Go. As an additional challenge, we exposed the agent only to synthetically-generated board images, rather than the raw underlying board state, to add a small vision component to the challenge.

We decided to employ a supervised-learning-only version of the original AlphaGo model. (Our system did not use reinforcement learning.) Broadly, this approach involves integrating learned search heuristics into a “Monte Carlo Tree Search” planning algorithm, thus leveraging both the fast-thinking NN “intuition”, and the slow-thinking tree-search planning.

The details are available in the write-up. In brief, we generated 10,000 “expert-play” games by pitting MCTS agents against each other. We then trained a “policy” network to predict which move the “expert” would play, and a “value” network to predict the likelihood that a given move in a given state would lead the player to victory. Finally, we augmented the MCTS algorithm to incorporate both of these heuristics in its tree-search process, which we dubbed “AMCTS”.

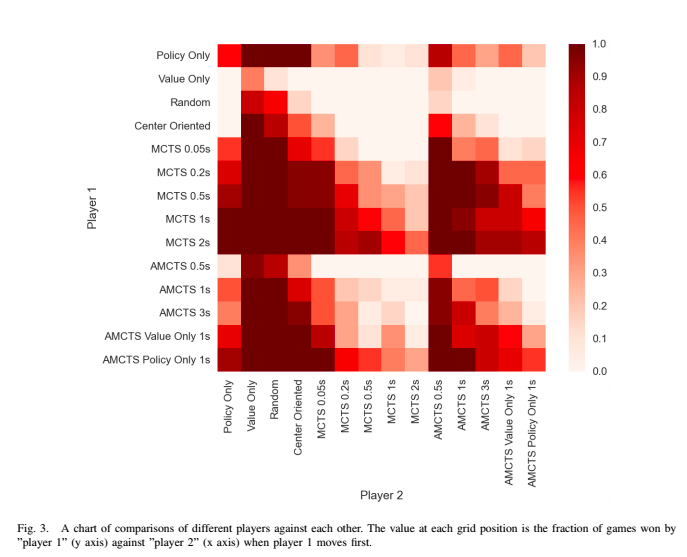

We then evaluated a slew of different agents against each other: a pure MCTS agent, an AMCTS agent, an AMCTS agent with only the “value” network, an AMCTS agent with only the “policy” network, a random agent, and more.

The head-to-head results are visible below.

The primary takeaway was, interestingly, that using supervised deep learning to play Connect Four is a bad idea. Pure MCTS consistently outperformed AMCTS with the learned heuristics added in, when both were given equal processing time.

This actually makes sense. Pure MCTS performs really well on Connect Four, which has only 7 possible actions per turn and at most a 40-move horizon. This means that pure MCTS can evaluate moves really quickly. On the other hand, AMCTS with the learned “policy” and “value” networks is substantially slower.

Thus, even though each rollout of pure MCTS is a less accurate/higher-variance evaluation of the board state than the smarter AMCTS, MCTS can execute many more rollouts per second than AMCTS can. As a result, the time wasted in computing the learned search heuristics leads to the AMCTS getting a much poorer evaluation of the state than the MCTS algorithm. This inevitably leads to far-degraded agent play.

Why didn’t AlphaGo encounter this same problem? Well, for starters, pure MCTS doesn’t work as well on Go, which has a much larger action space (an average 200 moves per turn) and a much longer game horizon than Connect Four. This means that MCTS rollouts are both more expensive and much-higher-variance estimators than in Connect Four. Simultaneously, Deepmind spent a lot of engineering effort to make the NN evaluations in AlphaGo as fast as possible, improving their modified MCTS’s number of runs per second. As a result, AlphaGo far outperforms regular MCTS on Go.

This was a fun project, both because it helped me better understand the design decisions behind AlphaGo, and because it helped me gain practical experience in learning for planning.

-Yo